Tibet is the ice-box of South Asia, with its myriad glaciers acting as major water-keeper for the entire region. With some 37,000 glaciers in Chinese-controlled Tibet alone, Lonnie Thompson, glaciologist at Ohio State University, calls the Himalayan region 'Asia's freshwater bank account'. It's an ice-box where massive buildup of new snow and ice (deposits) has traditionally offset its annual runoff in rivers (withdrawals). But now the region is facing bankruptcy, because rapid withdrawals are depleting the account. Of the 680 glaciers currently monitored by Chinese scientists, 95 percent are shedding more ice than they are adding, particularly at the southern and eastern edges of the plateau. The glaciers are not simply retreating, they are losing mass from the surface down, says Thompson.

The 'ice-box' is under siege by climate change, and by human interference. The latter includes rampant deforestation by Chinese loggers in eastern Tibet, the building of the railway to Lhasa (damage to permafrost), and building of mega-dams on most of Tibet's major rivers.

The ice and water resources in Tibet come in many forms:

- glaciers—thousands of them within Tibet: undergoing rapid melting due to climate change and human interference—in the form of CO2 emissions from China and India

- snowpack—when annual Indian monsoon rains hit Tibet, they are converted into snow—which settles on glaciers and thus makes monsoon rain usable over long periods as a meltwater source

- permafrost—a vast underground layer of permafrost is located across the Tibetan plateau: it is in danger of thawing (where the railway to Lhasa has been constructed, the permafrost is thawing faster)

- rivers—source of nine major rivers of South Asia plus many tributaries: all rivers are now being dammed by Chinese engineering consortiums

- lakes—numbering in the thousands: many are drying up due to climate change, encroaching desertification and human interference

- wetlands—also drying up and receding

- groundwater & springs—since the Lhasa train started up in 2006, bottled spring water has been shipped from Tibet to mainland China. Over a hundred spring sites have been identified across the Tibetan plateau.

Everest on Tap?

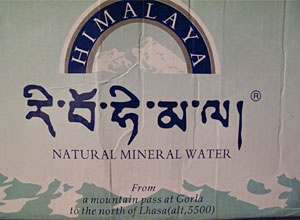

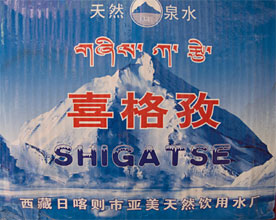

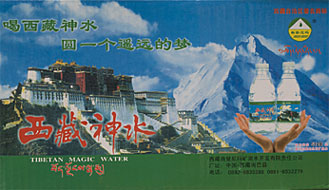

Close to Tingri, in western Tibet, is a water-bottling factory that claims to bottle Everest (Qomolangma) meltwater from a glacial source. As Everest north face is an iconic symbol for Tibet, it's not clear whether the source of this bottled water is right at Everest, or whether the company is using Everest as a branding device.

Certainly there is a lot of competition for using iconic Everest north face by other water bottling companies in Tibet—as the box labels below show.

Tibet's groundwater and spring-water was never tapped before 2005. Only since the completion of the Golmud-Lhasa railway in 2006 has it been economically feasible to export bottled water from Tibet, shipping it by rail as far afield as Shanghai or Beijing.

In late 2014, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology announced it would strongly support the growth of the natural drinking water industry in Tibet. To attract investors and entrepreneurs and boost sales nationally and overseas, major incentives were announced. Water manufacturers in Tibet will be exempt from all corporate tax for five years. They will be allowed bank loans at an interest rate 2 percentage points lower than the national average. Authorities are hoping to raise Tibetan natural drinking water output to more than 5 million metric tons by 2017 to 2019—an industry that could be worth 40 billion yuan—equivalent to US$6.4 billion. The head of the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology said: "The natural drinking water industry in Tibet has huge potential, based on the strength of public demand for safety and green consumption."

There is no doubt that Tibet has huge groundwater resources that have barely been tapped. But as for the "green consumption" part, very little chance of that happening. As Canadian water activist Maude Barlow puts it: "The bottled water industry is one of the most polluting industries on Earth, and one of the least regulated."

![]()

![]()

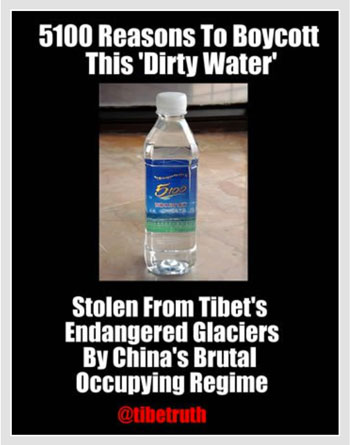

The prestigious 5100 brand

Is China concerned about melting glaciers in Tibet? Well, it seems entrepreneurs are more interested in tapping Tibet's glacial meltwater and putting it in plastic bottles as a status symbol. The Tibetan brand 5100 is served up in first-class and business on Air China flights. Tibet 5100 Glacier Spring Water has been heavily promoted by being handed out on high-speed trains (China Railway Express) and by being the official bottled water at high-level CCP events, such as the 60th anniversary of the founding of the CCP, which took place in 2009.

The source of 5100 is a spring at Damxung, about 170km north of Lhasa. The brand 5100 supposedly derives from the elevation of the spring. The processing plant is only 22km from the rail-line, and this is key to its success—as the bottled water is destined for export to east coast cities like Shanghai and Beijing. Without the railway, the venture would simply not work.

This is a joint-venture with Canadian-Chinese entrepreneur, Wallace Yu, whose company is headquartered in Hong Kong. Yu hopes to make 5100 a premium bottled water brand with an international reach—a sort of Chinese version of Perrier. In 2009, his company, Tibet 5100 Water Resources Holdings Ltd, produced almost two million gallons of bottled water, which was shipped out of Tibet by train, in a business estimated to be worth over $100 million a year. The water collected would otherwise flow through wetlands where yaks and sheep graze. It is not known how the factory's siphoning of water has impacted the ecosystem. Double whammy: plastic bottles are disastrous for the environment.

A single 330ml bottle of the "Tibet Spring" mineral water costs 7.5 yuan at retail in Shanghai or Beijing—about five times the price of a 550ml bottle from a non-premium company. So the 5100 brand appears to be aimed at China's rich, who fall for the hype that portrays the water as deriving from a pure source in the pure land of Tibet. Then again, knowing about China's environmental nightmares, what rich person would trust local brands of bottled water?

The venture hopes to establish 5100 as a world-class brand, with distribution assistance from Danish companies Carlsberg and Alectia. However, 5100 may run into some stiff resistance from Tibet support groups as tainted water.

exTreeeme weather

The annual monsoons in Asia and India used to be predictable. Today they are not. In 2010, way too much rain, with massive flooding in Pakistan and India, sent Pakistan into a crisis situation. At the edge of the Tibetan plateau, in Gansu province, massive mudslides killed thousands. This disaster can be directly attributed to rapacious Chinese loggers, who removed all the forest cover on the mountains in Gansu. But haywire monsoons—that is a different story. The 2009 annual monsoon in India was the worst in four decades: too late, too little rain.

Tidal surges in Bangladesh at the same time are the highest ever seen. Cyclones battering the coast of Bangladesh and southern India are becoming more frequent—and more vicious. The period 2009-2010 saw the worst droughts in Thailand in five decades, huge dust storms hammering Beijing, and rapidly expanding desertification in northern China.

Coincidence? or are these factors related to drastic changes on the Tibetan Plateau itself, altering jet-stream patterns? The Tibet Plateau drives jet-stream winds that influence seasonal weather patterns for millions. In fact, Tibet is the predominant driver of South Asia's annual monsoon winds, which deliver summer rains from eastern Pakistan to central China.