When the Ice melts in Tibet

Keeping Tibet's rivers in pristine free-flowing condition will be a challenge over the next decade. The highest percentage of water for these rivers comes from glaciers. Working against the rivers are rapid glacial meltdown and environmental degradation. Some experts believe that 75 percent of all Himalayan glaciers less than 15 square kilometres in size will simply vanish within the next three decades.

Bandaid-like 'fixes' to slow the rate of glacial meltdown revolve around bio-engineering proposals. One project under way in Ladakh in the western Himalayas explores ways of creating artificial glaciers. Retired civil engineer Chewang Norphel has built 'artificial glaciers'—which consist of simple stone embankments that trap and freeze glacial melt in the fall for use in the early spring growing season. In the Swiss Alps, bio-engineers are trying out 'glacier wrapping', which involves draping white insulation blankets over glaciers to protect the snow from the sun's rays in summer and thus slow the rate of melting.

High in the Peruvian Andes, a man called Eduardo Gold is trying to revive Chalon Sombrero Glacier, which melted away some time ago. He is doing this by transporting white paint on the backs of llamas up the 5,000-metre mountain-top. By painting the rocks white, he hopes to lower temperatures from 20 degrees Celsius down to 5 degrees Celsius, and thus attract ice build-up again. Seems like a Don Quixote absurdist effort, but there is a solid scientific principle behind it—called the Albedo Effect. By painting dark rocks white, less of the sun's energy is absorbed by the rocks and more is reflected away from the Earth, thus lowering the temperature of the rocks' surface.

China's Energy Technology

Technology to the rescue? Bio-engineering fixes? With China, it's the proverbial 'good news, bad news'.

Back in the 13th century, explorer Marco Polo reported to incredulous Europeans that Chinese peasants burned a 'black rock' for heat. Today, more incredulous news: burning these black rocks is destroying the planet. Lumps of coal burned in households in China result in a tremendous output of CO2 (not even taking industrial use of coal into account).

China has an insatiable appetite for energy, and has absolutely no plans to reduce its heavy dependency on coal-fired power plants, thus reducing its CO2 emissions. China is currently the top CO2 emitter in the world, with the US and India not far behind. This coal-fired energy is what drives China's economic miracle—its expanding economy. China builds an average one new coal-fired power plant a week. It is estimated that over 75 percent of China's energy demands are met by burning coal—the dirtiest fossil fuel in terms of emissions of greenhouse gases—but a mineral that China has in abundance. China is bent on preserving an important role for coal—at the expense of the environment. Dealing with climate change is not a priority here: official Chinese targets for capping CO2 emissions are vague. Bad for the air, coal is also bad on the ground: industrial use of coal for energy consumes large amounts of water.

Another key source of energy for China is oil and gas. Domestic oil and gas production cannot meet demand. In 2009, China surpassed the US as the biggest customer of Saudi oil and gas exports, and has been looking for ways of importing more of its oil via pipelines.

On the hydroelectric front, environmental considerations are not taken into account at all. China's current hydro engineering practices are highly destructive—they do not consider impact assessment for the local region, nor consider any negative implications for the nations downstream. China's water management practices are not sustainable.

These processes, once started, are next-to-impossible to reverse. Tibetan nomads could be brought back to act as stewards of Tibet's grasslands, with their grazing yaks, as they have done for centuries. The grasslands, if properly maintained by Tibetan nomads, would act as a carbon sink for heavy CO2 emissions hanging over the Himalayas. But this seems a very remote possibility. The decimated forests of eastern Tibet could be replanted to restore the balance of CO2 emissions, to prevent landslides and mudslides—and to prevent the region turning into a wasteland. There are no initiatives like this in progress.

Over the next decade, China is set to build more nuclear power stations than the rest of the world combined. However, while this may satisfy growing energy demand from within China, it doesn't solve the water crisis. Conventional nuclear fusion techniques consume mega quantities of water—and that water is returned to the rivers or lakes or seas much hotter after processing, with potential to trigger a whole slew of other problems (killing fish, for one thing).

“Ironically, the two countries building most of the new coal-fired power plants, China and India, are precisely the ones whose food security is most massively threatened by the carbon emitted from burning coal. It is now in their interest to try and save their mountain glaciers by shifting energy investment from coal-fired power plants into energy efficiency and into wind farms, solar thermal power plants, and geothermal power plants. China, for example, can double its current electrical generating capacity from wind alone.”

— Lester Brown, 2008

“The essential challenge is to design national energy policies to save the glaciers upon which Tibet, China, the Indian subcontinent and Indochina all depend. Right now China and India are pursuing a 'suicidal' economic policy of growth based on carbon fuels. In truth they need to cut carbon emissions by 80% as soon as possible. Asian civilization will not survive inaction or half-measures like partial decarbonization by mid-century. To date, proposals made by politicians for the convenience of the fossil fuel industry have no authentic bearing on the survival of billions of people, or civilization as we know it.”

— Dr John Stanley, Director of Ecological Buddhism, 2008

Solar and Wind Power

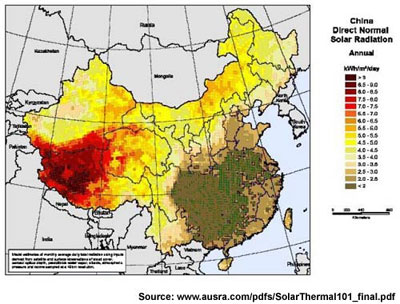

There are ways of generating power on the Tibetan plateau that do not involve building massive dams or the cutting down of entire forests for lumber. Outside of the Sahara, the Tibetan plateau has the greatest potential on the planet for harnessing solar energy. Due to Tibet's high altitude, the sun is very intense. Solar energy is most effective on the Tibetan plateau because of large areas of desert and clear skies. Much of China, by contrast, is cloudy or smoggy, allowing far less sun to penetrate.

In Tibet, there is also tremendous potential for harnessing wind power and geothermal energy on the plateau. However, these forms of energy are very expensive to generate when compared with hydropower. Currently, most of China's energy comes from coal-fired plants. Wind energy accounts for a minuscule amount of energy output—less than one percent.

China has embarked on an ambitious program of dominating global production of solar panels, with more than 400 solar-panel companies. It is also the biggest manufacturer and user of solar water heaters. And it is slated to become world number one in manufacturing technology for harnessing wind power. Wind power and solar power do not require any water consumption.

At the same time, however, China has become the world leader in big tunnel-making technology—and the world leader in mega-dam-building technology. The two technologies go hand-in-hand: tunnelling is critical to the building of mega-dams. This advanced tunnel technology was used in the construction of the railway to Lhasa—accomplishing a feat that was previously thought to be impossible to overcome due to permafrost instability.

Thermal map of China and Tibet, showing solar potential for Tibet

UHV Super Grid

State Grid Building in Lhasa

China is currently building an 800-kilovolt super grid that will connect all parts of the nation—in the most sophisticated transmission system for electricity the world has ever seen. All parts of the nation means Tibet. The new ultra-high-voltage lines can transfer power from the source up to 3,000 kilometres away. That means power generated by dams on the Tibetan plateau would be able to reach Chinese cities far to the east. Nearly 80 percent of China's water resources are in the southwest and Tibetan regions, and two-thirds of its coal is in three northern provinces, while demand centres for power are in coastal regions.

In June 2010, China Southern Power Grid, in a joint-venture with Siemens Energy (Germany) announced the opening of a UHV 800kV transmission line around 1,500 km in length. This link takes power from several hydroelectric plants in Yunnan province and transporting the energy to Guangdong Province, with its megacities Guangzhou and Shenzhen.

In August 2010, work started on electricity networking from Xining via Golmud to Lhasa. This line has a length of 1,744 km, including over 565km through permafrost terrain. This project consists of two main electricity networks: 750-kilovolt AC networking project on the Xining-Riyue Mountain-Wulan-Golmud route; and 400-kilovolt DC networking project on the Golmud-Lhasa route. Though billed as solving Lhasa's winter power shortage, the line in summer would export hydropower from Tibet north toward Xining and beyond. The line is expected to go into operation in 2012.

China has signed agreements with the government of Laos to set up a UHV super grid there—probably with an eye on exporting power to China.

Tibet UHV lines 2020:

Change from Within China

Certainly, something can be done to prevent human-engineered assaults on the rivers. Over the last few decades, China has embarked on a reckless dam-building spree across China. And China's engineers are now turning their attention to the Tibetan plateau—in a big way. These projects can be halted with a simple decision from Beijing. Dam damage can even be reversed: through de-commissioning of large dams (this has been done in California to allow salmon migration).

There have been a few success stories to counter dam-building in Sichuan, where many of China's new dams are under way. A project to dam Megoe Tso Lake in Ganzi Prefecture was scrapped due to pressure from local and international NGO groups. This was achieved on the basis that Megoe Lake is sacred to the Tibetans and is a key tourism attraction—and that its natural beauty should be preserved.

Another project halted on a similar basis was a proposed mega-dam at Tiger Leaping Gorge, on the Yangtse. A proposal was in place to construct a dam 276 metres high that would flood much of the spectacular Tiger Leaping Gorge scenic region, and would displace 100,000 Naxi people. In December 2007, it was announced that the project would be scrapped. However, it appears that the same project has been relaunched 60 km upstream under another name: Longpan Dam. If the dam at Longpan goes ahead, it will result in 100,000 people being forcibly relocated, and the inundation of 133 square kilometres of farmland.

Water Hero

The movement to halt the dam at Tiger Leaping Gorge was spearheaded by Yu Xiaogang. Yu founded the environmental group Green Watershed in 2002, as he worked to rebuild the area around Lashi Lake in SW Yunnan after a dam destroyed the local ecosystem. Since then, he has helped locals oppose a number of big-dam projects across China. The fate of Tibet's rivers lies with courageous figures like Yu Xiaogang, triggering change from within China.

China in 2060

Xi Jinping announced at the UN in September 2020 that China would be carbon neutral by 2060. He neglected to mention how this miracle would be achieved. In fact, China is going to depend heavily on hydropower expansion, viewing hydropower as green, clean, sustainable and renewable. Never mind that it destroys rivers and entire ecosystems in the process. This is the Green Dam Myth that China continues to push.

And where will this miraculous energy come from? To make China carbon neutral by 2060? Well, it comes heavily from hydropower—which China aims to DOUBLE by 2060. And since China itself is saturated with dams, the only place left to expand hydropower usage is Tibet—on the Yarlung Tsangpo for instance, and the Salween River.

And then, according to information sourced from China Report Asean, August 2021: from the year 2020 to 2060, the amount of electricity generated by solar would be increased 16-fold; wind power = 9-fold increase; nuclear power = 6-fold increase.

Damming by 2020

In August 2010, China surpassed the level of 200 gigawatts generated in hydro output. It took them 60 years of intensive damming to reach that level. And now comes an astonishing report from Shanghai Daily saying that the aim is to DOUBLE that output within the next decade to generate 430 gigawatts of hydropower by the year 2020. The rationale behind this is that hydropower is clean and this will reduce carbon emissions. In other reports, massive dam-building is also cited as a way to contain flooding—including flooding from glacial meltdown. Will the next ten years be a golden decade for hydropower? Or is this a disaster in the making?

The following report appeared in Shanghai Daily, January 6, 2011:

WITH 2020 clean-energy targets to meet, China is set to accelerate the building of hydroelectric dams, reversing a long halt caused by environmental concerns and the social upheaval of relocating people living in the shadow of dam sites. The trend will create a "golden decade" for the nation's hydropower sector, analysts say, as high fuel prices continue to squeeze margins of coal-fired power plants that comprise the bulk of China's electricity-generating capacity. Renewable energy sources like solar power have been slow to come on line on a big scale because of high costs and grid-configuration problems.

The Chinese government now aims to have 430 gigawatts of hydropower capacity by 2020, increasing its earlier target of 380GW, the China Securities Journal reported last month, citing unidentified sources. “That means each year, the equivalent of one new Three Gorges Dam will be added in China over the next decade,” said Shao Minghui, an analyst at China Post Securities, using the 2020 target of 380GW as a base. “The market is really sizable.” The 18.2GW Three Gorges Dam, which spans the Yangtze River and is located in Yichang, Hubei Province, is the world's largest.

A revision of targets in the 12th Five-Year Plan that starts this year calls for China to increase construction of conventional hydropower plants by about a third to 83GW and to raise the construction of pumped-storage hydro-capacity by 60 percent to 80GW, the China Securities Journal reported. The revision is pending approval before the National Development and Reform Commission.

In pumped-storage hydropower generation, water is pumped from a lower elevation reservoir to a higher elevation by using low-cost, off-peak electric power, and then is released to generate power during periods of peak demand or when electricity prices are higher.

China's hydropower generating capacity reached 200GW as of August, 2010 — accounting for more than a fifth of the nation's total power-generation capacity. The last operating unit to be added was in Yunnan province in China's southwestern corner. Shao estimated that the conventional hydropower sector will need an investment of 900 billion yuan (US$136 billion) by 2020, of which 140 billion yuan will be spent on equipment. This may benefit listed companies such as hydroelectric works contractor China Gezhouba Group Co and equipment supplier Ningxia Qinglong Pipe Industry Co.

China had planned to install 70GW of new hydropower projects as part of its 11th Five Year Plan, but construction was started on only about 20GW. Delays, especially of large-scale projects was mainly caused by the massive amount of human relocation the projects require and concerns about the environmental damage to surrounding landscapes. The government's attitude, however, appeared to be changing since the second half of last year. In July, China Huaneng Group and China Huadian Corp, two of China's main state-owned power groups, won clearance from the Ministry of Environmental Protection for major dams on the Jinsha River, the upper reach of the Yangtze River. In June 2009, the ministry had ordered a suspension in construction because of environmental violations. The National Development and Reform Commission in late October granted approval for China Three Gorges Corp to proceed with the early-stage of studies on its two planned power stations — one of 8.7GW; the other, 14GW — downstream on the Jinsha River.

In an interview with Xinhua news agency in August, Zhang Guobao, head of the National Energy Administration, reaffirmed the strategic role of hydropower as the best option for clean energy. Though China's hydropower capacity already ranks as the world's biggest, the utilization rate of its hydro resources still lags behind other countries. Zhang Boting, a vice secretary general of the China Society for Hydropower Engineering, said droughts in early 2010 in southwestern China confirmed that more hydropower facilities are needed in the nation. Analysts also agreed that hydropower would be one of the cheapest and most achievable ways to help China meet its clean energy consumption target.

In 2009, ahead of the Copenhagen climate change summit, China pledged to cut carbon intensity — or the amount of carbon dioxide produced for each unit of gross domestic product — by between 40 percent and 45 percent by 2020, using 2005 levels as the base. The government also aims to raise the proportion of non-fossil fuels in the nation's primary energy mix to 15 percent by 2020, from an estimated nine percent last year. Of the 15 percent, nine percent will come from hydropower and four percent from nuclear power, Zhang said. Other renewable sources, like wind and solar, lack competitiveness in terms of scale, economics and technology compared with hydropower in China. Zhang acknowledged that hydropower goals would be difficult to achieve, based on the approval status in the sector in recent years. He encouraged relevant agencies to accelerate the approval process, while still adhering to strict development rules.

The China Electricity Council, which represents the nation's power producers, also confirmed last month that the floodgates to build new hydropower projects are now open and the sector will enjoy priority status during the 12th Five-Year Plan. Projects will be mainly in mountainous southwestern provinces such as Yunnan and Sichuan, according to Ouyang Changyu, vice secretary general of the council.

“To expedite approvals, China must address the problems of environmental protection and people relocation,” said Zhou Yanchang, an analyst at Huatai United Securities. “And that will increase construction and operating costs.” One solution is to raise the price of hydropower electricity. At present, the on-grid tariff — or the price charged by power producers to grids — for hydropower is below that of energy produced by coal-fired plants. The prices are set based on operational costs of producing the power. Hydropower projects require larger investments and involve longer construction times than coal-fired plants, but they run at lower costs upon completion.

In September 2009, Zhang, the energy chief, said China aims to equalize hydropower prices with those of coal-fired electricity in the long term, though many hurdles remain to achieving parity between the two energy providers.